Mirogoj Cemetery, Zagreb, Croatia

In a field of black granite, an elderly couple bundled against the winter chill cleans the grimy remnants of a recent snowfall from their son’s final resting place.

In a field of black granite, an elderly couple bundled against the winter chill cleans the grimy remnants of a recent snowfall from their son’s final resting place.

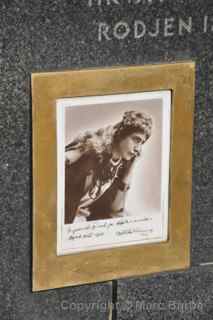

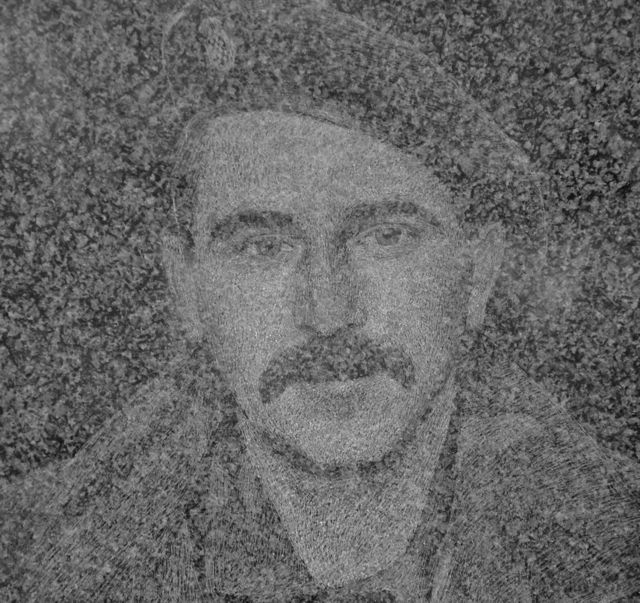

Using towels and a small bucket of water from a nearby spigot, they polish the flat grave ledger and the headstone with the young man’s laser-engraved likeness on it. Satisfied with their work, they arrange small bouquets of flowers, a few memorial candles, and an angel figurine at the headstone’s base.

Davor Šoban was only 24 when he was killed in 1992 fighting in the Croatian War of Independence.

Nearby, an auburn-haired woman performs similar tasks, shining a grave ledger until it sparkles in the sunlight and precisely positioning small vases of flowers, candles, and figurines of angels and the Virgin Mary around its gold-lettered markers: a headstone that includes the name of a soldier killed in the war in 1994 at age 26, and a separate heart-shaped stone with the likeness of a young man who died in 2002 at age 24 — maybe a brother or a nephew of the soldier.

Nearby, an auburn-haired woman performs similar tasks, shining a grave ledger until it sparkles in the sunlight and precisely positioning small vases of flowers, candles, and figurines of angels and the Virgin Mary around its gold-lettered markers: a headstone that includes the name of a soldier killed in the war in 1994 at age 26, and a separate heart-shaped stone with the likeness of a young man who died in 2002 at age 24 — maybe a brother or a nephew of the soldier.

After the woman finishes, she lingers. For the next half-hour, she sits in silence on the lip of the granite grave slab opposite her family’s, contemplating her losses, praying, and smoking an occasional cigarette.

Eventually she stands and gathers her cleaning supplies. She glances over her shoulder as she leaves for a final assessment of her work. Until next time.

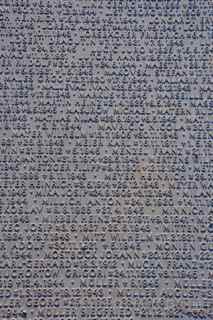

All around her, faces frozen in time and youth watch in silence, thanking her and other visitors for still remembering their sacrifices — for remembering them. These, too, are the heroes of the Croatian War of Independence, which left an estimated 20,000 dead from 1991 to 1995 as the breakup of Yugoslavia roiled the region in political and ethnic fighting.

All around her, faces frozen in time and youth watch in silence, thanking her and other visitors for still remembering their sacrifices — for remembering them. These, too, are the heroes of the Croatian War of Independence, which left an estimated 20,000 dead from 1991 to 1995 as the breakup of Yugoslavia roiled the region in political and ethnic fighting.

In this historic cemetery north of Zagreb’s city center, the final resting place of hundreds of thousands of famous and everyday Croatians, this entire section was added in the 1990s for victims of the war: servicemen, journalists, and civilians.

The cemetery’s first burial happened in 1876, its stunning north and south arcades were completed in the early 20th century, and lifelike sculptures watch over many graves in the old part of the cemetery. But these simpler, more uniform graves drew me back again and again as I walked paths that wound through acres of gently rolling hills. Runoff from the last traces of snow from a week or so earlier murmured like a fountain.

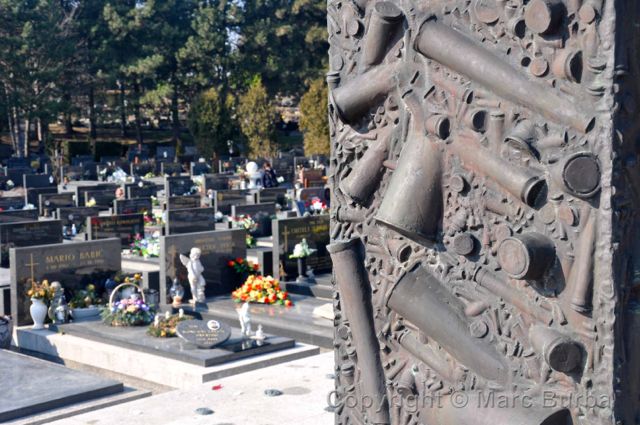

The soldiers’ graves are in the shadow of a towering golden cross atop a sculpted base of thousands upon thousands of bullets and shells — a symbol of their sacrifice. Even though the graves are at least two decades old, signs of frequent visitors abound. Floral arrangements, candles, figurines, and even toys crowd many of the slabs. They are not forgotten.

The soldiers’ graves are in the shadow of a towering golden cross atop a sculpted base of thousands upon thousands of bullets and shells — a symbol of their sacrifice. Even though the graves are at least two decades old, signs of frequent visitors abound. Floral arrangements, candles, figurines, and even toys crowd many of the slabs. They are not forgotten.