Bogotá, Colombia

Our first day here started with a pedestrian flying through the air.

Later, we took possession of an elderly blind man.

Bienvenido a Bogotá!

…

We really didn’t expect drama on a morning walk. We had just left our hotel and turned the corner onto a main road when we heard screeching tires and a thud. We turned as a man in a bright red sweater was launched about 10 feet, his body spinning as the red vegetables he carried flew in several directions. He landed shoulder first on the street and lay still for a few seconds.

We really didn’t expect drama on a morning walk. We had just left our hotel and turned the corner onto a main road when we heard screeching tires and a thud. We turned as a man in a bright red sweater was launched about 10 feet, his body spinning as the red vegetables he carried flew in several directions. He landed shoulder first on the street and lay still for a few seconds.

Two police officers materialized as I ran back to the hotel to summon an ambulance. It arrived within minutes. Attendants treated him where he lay and eventually helped him to his feet. He stepped into the ambulance on his own, with the crew holding his injured shoulder and arm.

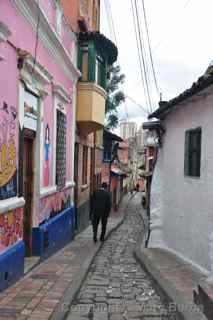

With the scene over, we headed to central Bogotá for our first visit to museums and historic buildings around Plaza de Bolívar. I guess that was the dull part of the day.

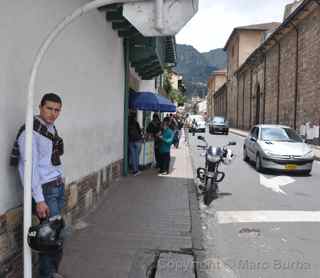

We set out on the same route that afternoon to find the city’s Hard Rock Café. A few blocks up, a security officer gruffly blocked our path and started talking — too quickly for people whose Spanish comprehension is pretty much limited to “Sí,” “No,” and “Más cerveza, por favor.” Even after our proclamation of “No hablamos Español,” he continued. Nearby a slight, elderly man wearing a gray jacket and a blue cap listened, his eyes hidden behind black-tinted sunglasses. The guard took him by the arm and led him over to us, putting his hand on my partner’s arm. He pointed north, where construction partially blocked the sidewalk, and then held up two fingers. Two blocks? Maybe. Through a few more gestures and words understood one by one among the four of us, we gathered that we had been enlisted to escort the man to find a taxi up the road.

I struggled to recall the basics of my high school Spanish classes to make conversation during the slow trip. That didn’t work well. But the man was patient, understanding, and appreciative anyway. Three blocks later, we still didn’t know exactly where we were taking him. So we found a street vendor who listened to his plight and then took over, leading him to what looked like a bus stop. We had walked right past it. We said goodbye, shrugged, and then walked on with our good deed fulfilled.

I struggled to recall the basics of my high school Spanish classes to make conversation during the slow trip. That didn’t work well. But the man was patient, understanding, and appreciative anyway. Three blocks later, we still didn’t know exactly where we were taking him. So we found a street vendor who listened to his plight and then took over, leading him to what looked like a bus stop. We had walked right past it. We said goodbye, shrugged, and then walked on with our good deed fulfilled.

…

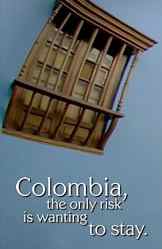

Sadly, Colombia’s reputation as a dangerous country overrun with armed rebel groups and ruthless drug cartels persists. The catchphrase on the country’s tourism Web site addressed that head-on: “Colombia, the only risk is wanting to stay.” The wave of horror tales does have an effect, though, even years later. My most vivid memory of this country had been the story of Elvia Cortez, who was abducted from her farm in May 2000. The kidnappers put a collar bomb around her neck and demanded a ransom. She died when the bomb exploded while a police technician tried to defuse it. He lost an arm, and three soldiers were wounded. I’ll never forget the photos that went out on news wires of her with a look of total hopelessness just before the bomb exploded.

Sadly, Colombia’s reputation as a dangerous country overrun with armed rebel groups and ruthless drug cartels persists. The catchphrase on the country’s tourism Web site addressed that head-on: “Colombia, the only risk is wanting to stay.” The wave of horror tales does have an effect, though, even years later. My most vivid memory of this country had been the story of Elvia Cortez, who was abducted from her farm in May 2000. The kidnappers put a collar bomb around her neck and demanded a ransom. She died when the bomb exploded while a police technician tried to defuse it. He lost an arm, and three soldiers were wounded. I’ll never forget the photos that went out on news wires of her with a look of total hopelessness just before the bomb exploded.

Today, though, the country is much different. Politicians in recent years have taken a stand against violence. We never felt unsafe walking around Bogotá, which has a strong police and security presence. We took the advice of hotel staff and local guides on places to avoid for fear of crime, but we do that in any large city we visit. Just like Cambodia or any place where there’s been unrest or war, there’s a stigma that has to be overcome. We did our research, and we’re glad we visited.

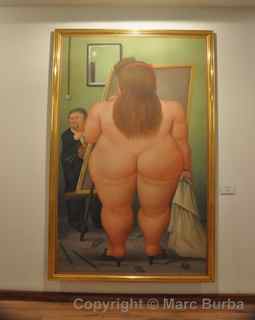

If we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have been introduced to the works of Fernando Botero. I’m not really a museum fan, and I find a lot of them to be boring. The free Museo Botero in central Bogotá was an exception, much like the great museums of Oslo. The Colombian painter and sculptor established the museum in 2000 and donated his extensive collection. The portraits and still lifes are exaggeratedly large and oddly interesting. Visitors are meant to have fun, and they can take photos of and with many of the paintings and sculptures. Docents are close by to keep visitors in line, but this place never feels pretentious. It really has a great vibe. The museum is part of a connected complex that also houses a coin museum and other art collections.

If we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have been introduced to the works of Fernando Botero. I’m not really a museum fan, and I find a lot of them to be boring. The free Museo Botero in central Bogotá was an exception, much like the great museums of Oslo. The Colombian painter and sculptor established the museum in 2000 and donated his extensive collection. The portraits and still lifes are exaggeratedly large and oddly interesting. Visitors are meant to have fun, and they can take photos of and with many of the paintings and sculptures. Docents are close by to keep visitors in line, but this place never feels pretentious. It really has a great vibe. The museum is part of a connected complex that also houses a coin museum and other art collections.

We got an idea what a sprawling city of 7 million people looks like from above with a funicular ride to Monserrate Peak. A church with an almost 400-year-old altar statue of the Fallen Christ, souvenir and food stalls kept us busy on a Sunday as we mingled with the many pilgrims the church draws on weekends.

We got an idea what a sprawling city of 7 million people looks like from above with a funicular ride to Monserrate Peak. A church with an almost 400-year-old altar statue of the Fallen Christ, souvenir and food stalls kept us busy on a Sunday as we mingled with the many pilgrims the church draws on weekends.