California: The Salton Sea

It’s as predictable as sunrise and sunset: Each winter, the snowbirds begin their migration from cold, northern states and Canada to the Southern California desert. Flocks of them crowd in, making the sleepy desert come to life.

It’s as predictable as sunrise and sunset: Each winter, the snowbirds begin their migration from cold, northern states and Canada to the Southern California desert. Flocks of them crowd in, making the sleepy desert come to life.

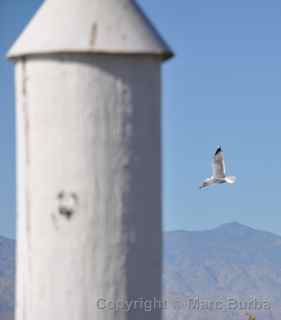

We saw a lot of snowbirds on this weekend. A good number of them were driving their cars and RVs to the Salton Sea to check out the wildlife.

In desert-speak, snowbirds are seasonal residents who have second homes in the Coachella Valley. License plates from Montana, Washington state, and even British Columbia are as common as California tags during winter and spring months. Many of these people are retirees, and some probably even remember the days when the accidental lake in the middle of the desert — 226 feet below sea level — was a bustling resort area in the mid 20th century. Those days are long gone, and the sea now is more known for its smell and its annual fish die-offs. The entire area has been dying for decades, though some proud people and those without the means to go anywhere else still call the collapsing communities around the sea home.

In the years I lived in Southern California, I had never visited the sea, even though I could see it from the top of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway 50 miles away. It’s also visible from just about any East Coast flight into or out of a Southern California airport. I smelled it often enough — once or twice a year, the stench of gases from decomposing algae drifts over the entire Coachella Valley, sometimes lingering for days.

In the years I lived in Southern California, I had never visited the sea, even though I could see it from the top of the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway 50 miles away. It’s also visible from just about any East Coast flight into or out of a Southern California airport. I smelled it often enough — once or twice a year, the stench of gases from decomposing algae drifts over the entire Coachella Valley, sometimes lingering for days.

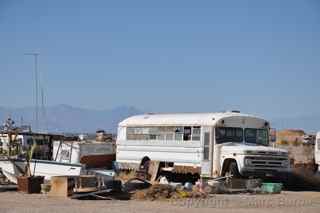

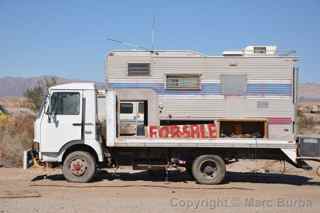

But it’s interesting to see what happens to a place that the world seems to have left behind. Long-abandoned buildings and vintage travel trailers literally fall apart on junk- and tumbleweed-strewn lots. Cars from the 1950s and ’60s fade under the relentless sun. The poverty level here is about 39 percent, according to U.S. census data.

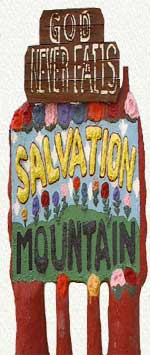

This is where the colorful mound known as Salvation Mountain is located. Folk artist Leonard Knight’s tribute to God painted on a self-made adobe and straw “mountain” is in the middle of the desert between Niland and “Slab City.” It has stood, collapsed, and stood again at this remote site since the 1980s, and has withstood an attempt by the Imperial County government to declare it toxic and raze it, after a public outcry made the government back off. People stop by to climb on and photograph the artwork, which is surrounded by a collection of junked cars and trucks painted with rainbow-colored biblical messages, and hundreds of paint cans and buckets that remain as a testament to his work.

This is where the colorful mound known as Salvation Mountain is located. Folk artist Leonard Knight’s tribute to God painted on a self-made adobe and straw “mountain” is in the middle of the desert between Niland and “Slab City.” It has stood, collapsed, and stood again at this remote site since the 1980s, and has withstood an attempt by the Imperial County government to declare it toxic and raze it, after a public outcry made the government back off. People stop by to climb on and photograph the artwork, which is surrounded by a collection of junked cars and trucks painted with rainbow-colored biblical messages, and hundreds of paint cans and buckets that remain as a testament to his work.

Knight lived for years in the back of an old truck on the land, painting when the days weren’t too hot or the nights too cold. According to an online history of the site, he has used about 100,000 gallons of paint on the mountain. Sadly, his work here has stopped. In late 2011, the 80-year-old man was admitted to a long-term care facility. He died Feb. 10, 2014. A group of volunteers is working to protect and maintain the site.

Just up the road is Slab City, which is basically a squatters camp that takes shape each year around the concrete slabs that remain from Camp Dunlap, a World War II-era Marine barracks. A collection of RV, old bus, and trailer dwellers live off the grid, with no running water or other utilities. Many use solar panels or generators for electricity. Jon Krakauer described the place best in his book “Into the Wild:” “The Slabs functions as the seasonal capital of a teeming itinerant society — a tolerant, rubber-tired culture comprising the retired, the exiled, the destitute, the perpetually unemployed. Its constituents are men and women and children of all ages, folks on the dodge from collection agencies, relationships gone sour, the law or the IRS, Ohio winters, the middle-class grind.”