Pécs, Hungary

A snowstorm could have ruined a tourist’s day. For me, it was simply a chance to duck inside.

The train bound for Pécs pulled out of Budapest’s Keleti station at zero-dark-forty-five. I knew there was a chance for light snow on this day, but Budapest was dry when I left. City lights quickly faded to the blackness of the Hungarian countryside. I could see nothing in my window but the dim, reflected light from my passenger compartment.

About 45 minutes into this three-hour trip south, though, I noticed a bluish glow outside. It wasn’t daylight yet — still too early for dawn to break. Then the train passed a rural road crossing, and in the headlights of stopped traffic I saw swirling snow. It had already covered the fields, and was accumulating on roads. The blue glow became bright white in daylight. Deer, sometimes in herds of a dozen, foraged for food near the tracks. Occasionally one would get too close — after a sharp horn blast, I would see one bounding down a slope into the tree line. A few rabbits and even a fox also poked out of the accumulating powder. By the time the train stopped in Dombóvár, about 30 miles north of my destination, several inches had fallen.

About 45 minutes into this three-hour trip south, though, I noticed a bluish glow outside. It wasn’t daylight yet — still too early for dawn to break. Then the train passed a rural road crossing, and in the headlights of stopped traffic I saw swirling snow. It had already covered the fields, and was accumulating on roads. The blue glow became bright white in daylight. Deer, sometimes in herds of a dozen, foraged for food near the tracks. Occasionally one would get too close — after a sharp horn blast, I would see one bounding down a slope into the tree line. A few rabbits and even a fox also poked out of the accumulating powder. By the time the train stopped in Dombóvár, about 30 miles north of my destination, several inches had fallen.

Pécs, too, was covered in several inches when I arrived. Sidewalks from the train station to the city center were slushy and slick. Shopkeepers had started clearing paths in front of their businesses and a young mother pulled her toddler on a sled in a main square. But for me, even bundled up it was too cold to stay outside for too long.

Pécs, too, was covered in several inches when I arrived. Sidewalks from the train station to the city center were slushy and slick. Shopkeepers had started clearing paths in front of their businesses and a young mother pulled her toddler on a sled in a main square. But for me, even bundled up it was too cold to stay outside for too long.

So, after a bone-chilling couple of hours walking around to see the snowy sights, I bought a museum pass for the equivalent of $15 that gave me access to nine museums. I focused on three, and stayed busy and warm for a while.

So, after a bone-chilling couple of hours walking around to see the snowy sights, I bought a museum pass for the equivalent of $15 that gave me access to nine museums. I focused on three, and stayed busy and warm for a while.

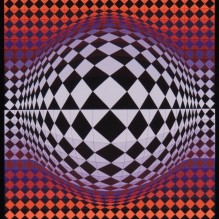

I was introduced to Tivador Kosztka Csontváry, a Hungarian avant-garde painter who died in relative obscurity in the early 20th century but whose works now hang in the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and here, in a museum dedicated to him. I learned that the leader of the op art movement, Victor Vasarely, was born here. A museum is dedicated to his works and those of other optical illusion artists. And I discovered that the colorful, glazed roof tiles that adorn the stunning Matthias Church in Budapest were made here by the 150-year-old Zsolnay company that perfected iridescent glazes and durable frost-resistant pyrogranite for buildings and ornamentation. Back at home, I have two Matthias Church roof tiles from an early 2000s restoration project that are, in fact, authentic Zsolnay tiles.

I was introduced to Tivador Kosztka Csontváry, a Hungarian avant-garde painter who died in relative obscurity in the early 20th century but whose works now hang in the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and here, in a museum dedicated to him. I learned that the leader of the op art movement, Victor Vasarely, was born here. A museum is dedicated to his works and those of other optical illusion artists. And I discovered that the colorful, glazed roof tiles that adorn the stunning Matthias Church in Budapest were made here by the 150-year-old Zsolnay company that perfected iridescent glazes and durable frost-resistant pyrogranite for buildings and ornamentation. Back at home, I have two Matthias Church roof tiles from an early 2000s restoration project that are, in fact, authentic Zsolnay tiles.

My final stop was a work of art in itself: the Gazi Kasim Pasha Mosque, built in the late 1500s by Ottoman invaders who razed a church on the site and used its stones in this construction. When the Ottomans were driven out a century later, it became a church again, and the Islamic and Christian elements were blended. Stepping inside reminded me of my visit the year before to Istanbul.

My final stop was a work of art in itself: the Gazi Kasim Pasha Mosque, built in the late 1500s by Ottoman invaders who razed a church on the site and used its stones in this construction. When the Ottomans were driven out a century later, it became a church again, and the Islamic and Christian elements were blended. Stepping inside reminded me of my visit the year before to Istanbul.

Pécs is a beautiful city, even when delicate outdoor fountains are covered to protect them from the cold, and repair scaffolding surrounds its landmarks, and snow shrouds its streets. I hope I can return someday to enjoy it from the outside.